The Great Dynamite Factory a Ardeer

McClure’s Magazine ~ August 1897 By H. J. W. Dam

The making and handling of High Explosives

Life and Manners of the workmen

Precautions against accidents

The small number of casualties

The great dynamite factory at Ardeer in Scotland, the largest of its kind, is one of the most picturesque places in the world. Considering the unique and dramatic conditions that prevail amongst its workers, the neglect of Ardeer hitherto by novelists and dramatists is surprising. This may be due, however, to the fact that it is exceedingly difficult for a stranger to obtain access to the factory, while, once inside, the surroundings are rather trying to sensitive nerves. For six hours a day and two days in succession your life depends, at every moment, upon a thermometer.

Great is the thermometer at Ardeer! Nitroglycerin, a teaspoonful of which would blow you to fragments, surrounds you in hundreds and thousands of gallons. It is making itself in huge tanks, gurgling merrily along open leaden gutters, falling ten feet in brown waterfalls, so to speak, into tanks of soda solution, and bubbling so furiously in other cylinders, through the in-rush of cold air from below, that it seems to be boiling.

It is being draw off from large porcelain taps like ale, poured into boxes, and rattled along tramways. In the form of dynamite, it is being rubbed with great force through brass sieves, jammed into cartridges, and flung into boxes; and in the form of blasting gelatin, it is being torn by metal rods, forced through sausage machines, and cut, wrapped, and tossed into hoppers - all these processes proceeding as rapidly as if it were ordinary olive-oil instead of the deadliest explosion known to man.

All around you are big cotton mills and storehouses as full of fleecy, white cotton as ordinary cotton mills and storehouses, but every pinch of the cotton, still white and fleecy, has been nitrated into gun-cotton, and would suffice, if explode, to cut you off in the beauty of your youth. Death instantaneous and pulverizing, encircles you, in fact, by the ton; but the man and the thermometer surround you also. The man’s eyes never leaves the instrument.

Both are chosen for their perfect reliability; and endless precautions, innumerable rules, and the strictest discipline maintain Ardeer in a state of busy and peaceful security, and prevent it from being scattered periodically over the calm blue sea that widens endlessly on one side, or the hungry brown acres of Scotland which stretch away to the horizon on the other.

Both are chosen for their perfect reliability; and endless precautions, innumerable rules, and the strictest discipline maintain Ardeer in a state of busy and peaceful security, and prevent it from being scattered periodically over the calm blue sea that widens endlessly on one side, or the hungry brown acres of Scotland which stretch away to the horizon on the other.

From the top of one of the Nitroglycerin hills the factory looks like an enormous and eccentric landscape garden. In every direction rise green embankments, square, conical, or diamond-shaped, from fourteen to seventy feet in height, and covered with long rank grass. Many of them are faced with corrugated iron, and look like high fences. From the top of each mound peeps the red canvas roof of a white wooden house – a house within a hill – which is from one to four stories in height. Every explosive structure is surrounded by artificial banks, so that in the event of an accident all the others will be protected from concussion or flying fragments.

There are three nitroglycerin hills; and on the one before you the nitrating-house, two in number, in which the nitroglycerin is made, stand out in clear relief at the top. They are frail wooden cabins, which were expected by Mr Nobel when he built them to last six months, but which have not yet been blown to pieces after twenty-five years of constant use.

Tunnels through the banks open everywhere. Tramways and lines of pipes on trestles cross each other diversely. This is the "Danger Area," the wide expanse in which the explosives are made and moved about. It is surrounded in an irregular semicircle by fourteen large groups of structures, from which rise fourteen large chimney-stacks. These include the nitric-acid works, acid recovery, ammonia-mill, potash-mill, "guhr"-mill, steam and power houses, box-factories, washing, carding, and bleaching departments for the cotton, pulping-mills, and other contributing industries, connected by the steam railway tracks which join the Glasgow line.

There are 450 separate structures, now occupying 400 acres out of the 600 owned by the company, which were, when the site was chosen by Mr. Nobel in 1871, a barren waste of sand dunes, stretching for a mile and three-quarters along the sea.

Into this kingdom of high explosives you enter by the courtesy of Mr. C. O. Lundholm, the works manager, under the guidance of the engineer of the works, Mr. E. W Findlay. The strain upon your nerves begins mildly. Your hair is quite ready to rise, so ready that you can feel it awake and stretch itself at every spot of grease which may be nitroglycerin - and every stray pinch of cotton - which may be gun-cotton.

You now understand for the first time the psychological condition of a shying horse. You go along just as the horse does, with eyes strained at every small object and a lurking predisposition to bolt.

The acid-works are soothing, however. They are quite safe. Nitroglycerin is made from glycerin, the sweetish adjunct of the dressing table, and nitric acid. The glycerin is bought by hundreds of tons from various sources. In this big barn which you enter the nitric acid is manufactured. In two rows stand fifty-eight steel retorts about six feet in diameter and four feet deep, which are bricked up like ovens.

Here sulphuric acid, or oil of vitriol, from Glasgow is combined with nitrate of soda from Chili, and the nitric acid thus set free passes over in the pipes to a high framework carrying numberless brown earthenware jars in which it condenses. As it passes over it gives off red – dish fumes which are suffocating - a whiff of them gives you a fit of coughing, and a full breath of them would choke a locomotive.

Mr. Findlay explains that the nitric acid thus made is mixed with a larger quantity of sulphuric acid, and removed in steel pony-cars to a station at the foot of each nitroglycerin hill. Thence the acids are drawn up by cable or blown up through pipes to a tank at the top of the hill by compressed air. You mentally compare the advantages of being blown up with compressed air to be blown up by other means, and smoothing down your hair, enter the Danger Area.

The Danger Area

To enter the "Danger Area" you must pass the searcher. He stands in front of his cabin, and you will find one of him always blocking the way at the four entrances to the explosive district. He is a tall, military-looking man in a blue uniform faced with red, and he takes from you all metallic objects - your watch, money, penknife, scarf-pin, match-case, matches and keys. None of these are allowed to be where nitroglycerin is.

To enter the "Danger Area" you must pass the searcher. He stands in front of his cabin, and you will find one of him always blocking the way at the four entrances to the explosive district. He is a tall, military-looking man in a blue uniform faced with red, and he takes from you all metallic objects - your watch, money, penknife, scarf-pin, match-case, matches and keys. None of these are allowed to be where nitroglycerin is.

He searches every man who enters, no matter how often the man may come and go, The girls, 200 of whom are employed, are not permitted to wear pins, hair-pins, shoe-buttons, or metal pegs in their shoes, or carry knitting, crochet, or other needles. These regulations are the outgrowth of experience and the long-ago discovery in dynamite cartridges of buttons and other foreign substances calculated to make trouble at unexpected moments. The girls are searched thrice a day by the three matrons who have them in charge. From the lack of hair-pins they wear their hair in braids, tied with ribbons, which gives them all an unduly youthful look. The searcher tells you that his chief trouble is with matches.

Some of the lower-class male employees – there are 1,100 men in the factory – are willing at times to smuggle in matches for a quiet smoke in a secluded corner. This quiet smoke may of course produce a much louder smoke in a corner not so secluded, and is therefore rigidly banned. The discipline in the factory is most extraordinary, and to it must be attributed the marvelous immunity from accidents.

At this point, too, you get your first glimpse of the "costumes." A man in a Tam O’Shanter cap comes up clothed from head to foot in vivid scarlet. He belongs to a nitroglycerin house. Then comes a man in dark blue, a "runner" or carrier of explosives.

Then comes a man in light blue, who belongs to a smokeless-powder factory. All the girls are in dark blue. The different colours are used so that a superintendent at any distance can always tell if a man is on his own ground and attending to his own work.

A few weeks since, a cartridge lassie in dark blue said to a man in scarlet, "Gi’e us a kiss," and he promptly gi’ed her one. This unlawful combination of colours caught the eye of an overseer hundreds of yards away, and the pair were instantly removed from the works and the pay-roll.

Kissing and skylarking are absolutely prohibited during working hours, but on Saturday and Sundays the workers make full amends. If reports are to be believed, the workers are more than usually romantic in their tendencies, the alleged cause being the constant breathing of nitroglycerin; and inquiring Pickwicks have taken many notes there upon, in which the statistics of marriage and population are not entirely neglected.

The Nitrating House

Having passed the searcher, you mount the hill, an artificial one built of sand, and perhaps sixty feet high. On the top of it are two "nitrating houses." They are of thin clapboards painted white, and are about twenty feet square. These houses are always placed on the tops of hills, in order that the nitroglycerin, passing from process to process, may flow by its own weight downward.

Having passed the searcher, you mount the hill, an artificial one built of sand, and perhaps sixty feet high. On the top of it are two "nitrating houses." They are of thin clapboards painted white, and are about twenty feet square. These houses are always placed on the tops of hills, in order that the nitroglycerin, passing from process to process, may flow by its own weight downward.

It is not exactly the kind of liquid that one wants to pump. At the door of the house you are confronted by two pairs of yawning rubber shoes. Large shoes of rubber, indeed, and sometimes even larger ones of leather confront you at the door of every danger house. No shoe which touches the ground outside is allowed to touch the floor of a danger department. The least grit might make friction and lead to an explosion.

In all departments the girls are compelled to change to slippers or work barefooted, the majority, in summer, preferring the latter. Having stepped into the overshoes, you begin to flop like a great auk over the sheet-lead which covers the floor. The shoes are trying, particularly as you have other things to worry you. Snow-shoes, ski, and stilts can all be practiced on with advantage before endeavoring to get about in a pair of overshoes which do not fit your own shoes and are ceaselessly trying to trip you up.

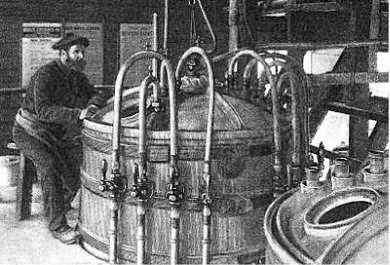

As you enter the nitrating-house your eye is caught by two lead cylinders, five feet in diameter and six feet deep, which are sunk in the floor. They have closed, dome-shaped tops, over which many lead pipes curl and into which enter. At the farthest cylinder sits a man in scarlet watching a thermometer. He neither moves, looks up, nor betrays any sign of your presence.

The thermometer which he is watching is five feet in length. Only the top or marked portion extends above the cylinder, the tube which carries the mercury reaching down to the hot acids and nitroglycerin. In the cylinder has been has been placed about a ton and a half of sulphuric acid mixed with a ton of nitric.

Into this mixture are now being sprayed 700 pounds of glycerin, the glycerin injector-pipe being joined by another carrying compressed air. As fast as the glycerin spray enters the mixture it seizes the nitrogen of the nitric acid and combines to nitroglycerin, and the sulphuric takes up the water which is thus set free.

The process requires fifty-five minutes, during which the 700 pounds of glycerin becomes about 1,500 of nitroglycerin. Great heat is caused by the chemical action, and the absolute necessity is that the heat shall be kept down or it will explode the newly formed nitroglycerin.

To this end the cylinder is surrounded by a water-jacket, through which cold water is rushing constantly, and four concentric coils of lead pipe occupy the interior of the cylinder, carrying four steady rushes of cold water. If the heat, through vagaries in the glycerin, rose above the danger point, the thermometer would instantly reveal this to the man on watch.

If the thermometer rose ever so little above twenty-two degrees centigrade, the man would turn on more air and shut off the inflow of glycerin. If it continued to rise slowly and he could not stop it by more air and water, he would give a warning shout, "Stand by," to a man watching below.

If it continued, he would shout "Let her go," and the man would open a valve; this would sweep the whole charge down to the "drowning-tank" lower down the hill, which would drown the coming explosion in excess of water.

The two men the meanwhile would bolt to a safe position behind banks. If the heat rose rapidly, too rapidly for "drowning," the man would pull the valve, give a warning shout and run. So would everybody, you included. You might run on one side to the protecting arms of a dynamite magazine holding twenty tons, or on the other to the soothing shelter of a house where gun-cotton is baking at 120 degrees Fahrenheit.

Failing these, there is the pond. This is a sweet placid pond which is formally blown up once a week because some dregs of nitroglycerin have drained into it and collected at the bottom, making it unsafe. It is comforting to feel, in the hour of danger, that you have havens of perfect security such as these.

The glycerin having duly become nitroglycerin, you flop down the stairs to another department, to witness separation from the acids with which it is now mixed. It comes shooting down a lead gutter, and falls, a cream-coloured stream, to the bottom of a lead tank, eight feet in length and two in width.

As soon as the tank is full, the nitroglycerin, lighter than the acid, rises to the surface like oil. It is skimmed off in an aluminium skimmer resembling a tin wash-hand basin with a handle, and is poured into a lead pocket at the end, whence it flows through pipes to a tank, where it receives its first washing with cold water. Thence it goes gutters further down to another department, where it is washed with warm water and carbonate soda.

Every particle of free acid must be removed, as remnants of it might cause chemical action, heat, and explosion in the dynamite or blasting gelatin later on. A sample is taken of each lot of nitroglycerin when mad.

This is placed in a small clear glass bottle and covered with blue litmus solution, to detect the presence of any remaining free acid, which would colour the litmus red. En passant, your guide mentions that some years ago one of the foremen was carrying a little felt-lined box of theses samples to one of the sample magazines when he unfortunately stumbled and fell. He was blown to pieces.

You have now reached the bottom of the hill (all nitroglycerin factories are called hills) and are in a wooden cabin, with a floor of loose sand, where the making of dynamite and blasting gelatin actually begins.

Dynamite consists merely of liquid nitroglycerin which has been absorbed by some porous material. The liquid was discovered by Sobrero, an Italian, in 1846. Its transport and use were attended with such danger, however, that the late Alfred Nobel conceived, in 1867, the plan of absorbing it in some non-explosive medium. After experimenting with saw-dust, brick-dust, charcoal, paper, rags, and kieselguhr, he finally settled upon the last named as the best material.

Dynamite consists merely of liquid nitroglycerin which has been absorbed by some porous material. The liquid was discovered by Sobrero, an Italian, in 1846. Its transport and use were attended with such danger, however, that the late Alfred Nobel conceived, in 1867, the plan of absorbing it in some non-explosive medium. After experimenting with saw-dust, brick-dust, charcoal, paper, rags, and kieselguhr, he finally settled upon the last named as the best material.

Kieselguhr, known in the factory as "guhr," is a silicious earth, mainly composed of the skeletons of mosses and microscopic diatoms, which is found as a slaty black peat in Scotland, Germany and Italy. Before being used it goes to the guhr-mill, where it is calcined in a large kiln, rolled, and sifted, the result being a very light pink powder of the consistency of flour.

In the house you have entered, twenty-five pounds of kieselguhr, with one pound of carbonate of ammonia, are weighed into a wooden box about three feet square and eighteen inches deep. Upon it is drawn seventy-five pounds of nitroglycerin from the filter tank by a man in scarlet. Another man in scarlet, with his arms bare to the shoulders takes the box to a table, and gives it a preliminary mix, to see that all the nitroglycerin is roughly absorbed. Then a man in blue seizes it, places it with other boxes on his hand-car or bogie, and pushes the load off to the mixing houses.

A Disastrous Explosion – The Mixing Houses

At half-past six on the morning of the 24th February, one week after the writer’s visit to this house, it was the scene of a very disastrous explosion. Twenty-four hundred pounds of nitroglycerin was collected here, in the tanks and boxes mentioned, and from some cause which may never be known it exploded, killing six people – a chemist, a foreman, and four workmen.

A few other employees were slightly hurt by flying debris. The sound of course was tremendous, and the effects of the explosion, which were very clear in Irvine, three and one half miles away, are said to have been so strong in a town ten miles away that the gas lamps were extinguished by the air concussion. A disaster such as this, whose suddenness is not its least painful characteristic, cannot of course be minimized in its tragic importance.

At the same time, it serves as the best possible testimony to the value of the system of protection employed, That over a ton of nitroglycerin can explode in the heart of a factory where 1,300 people are at work, and only six men, within a few feet of it, lose their lives, shows better than any other evidence the meaning and value of the Ardeer mounds.

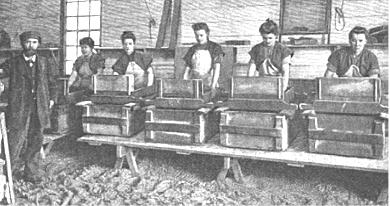

You follow the box to a mixing house, this, in the case of dynamite, is a large wooden cabin, containing a long narrow table on each side. In it six girls are at work. The runner sets the open box of the mixture down in the doorway. A girl hoists it to a table, and flies at it with bare arms as if it contained flour and water.

She mixes it thoroughly. Then she takes a big wooden scoop, jabs it into the box, and dumps the scoopful into a raised box of the same size, with a brass sieve bottom. She then, as if the sieve bottom were a washing-board, rubs the dynamite with all her strength against the sieve, forcing it through the small holes. A few of the girls use a leather hand-flap to rub with, but most of them prefer their bare hands.

You view the process with consternation. Hitherto you have looked upon dynamite as something to be regarded politely from a safe distance as if it were a rattle-snake. The girls handle it, however, as coolly as if it were the sand on the floor. Some of it is continually split, of course, and mixes with this sand, but the sand is all removed at short intervals and buried.

One of the few fatal accidents in the history of Ardeer took place near this house. A cartridge hut wherein four girls were working exploded, killing the girls. Burning dust from this hut fell into open boxes of dynamite in three other huts. The dynamite began to blaze, and deadly smoke from it, which consists of hyponitric-acid fumes, immediately filled the huts. Two girls in each had the courage to jump over the blazing boxes, and escaped; but the others, six in number, were suffocated in a few minutes. Thus ten persons lost their lives.

When the huts were entered, the six girls were found seated in perfectly natural attitudes, their faces showing no trace of agony or fear. It was evident that, having been stunned by the sudden explosion, they had suffocated before recovering from the shock. It will be noted that the loose dynamite burned and did not explode. This is one of several curious facts concerning dynamite which will be considered later.

It may be well to state at this point that the two hundred and odd young ladies employed in this dangerous work are all strictly beautiful. Everybody who visits the factory admits this at once. Nobody, in fact, seems inclined to invidious comparisons among strong and courageous girls, when each of them has enough dynamite in her possession to blow a hole in Scotland. Moreover, there is some reason for the statement.

The breathing of nitroglycerin by the workers gives them a universal clearness of skin, and among the fairer girls the contrast of scarlet and white in their faces is most unusual. You learn that (perhaps in consequence of their complexions) the girls marry quickly after entering the factory.

The Cartridge Houses

After being rubbed through the sieves the dynamite becomes a finely divided greasy, coffee-colored earth. It is now the dynamite of commerce, and is ready to be made into cartridges. As you approach one of the cartridge houses, which are small white one-story buildings, you hear a tremendous thumping. You ask your guide in some perturbation if it is a good day to at cartridge houses, but he smiles and says that the noise is merely the cartridge machines.

After being rubbed through the sieves the dynamite becomes a finely divided greasy, coffee-colored earth. It is now the dynamite of commerce, and is ready to be made into cartridges. As you approach one of the cartridge houses, which are small white one-story buildings, you hear a tremendous thumping. You ask your guide in some perturbation if it is a good day to at cartridge houses, but he smiles and says that the noise is merely the cartridge machines.

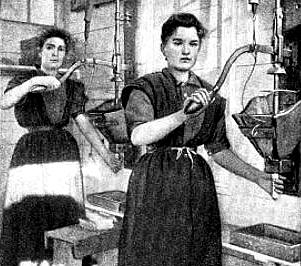

The hut is about ten feet square, with a single door. Four girls are at work. Against the right and left walls are four spring pump-handles about the weight of a girl’s head. Each pump handle when pulled down forces a brass rod through a small conical hopper of loose dynamite fixed to the wall, and jams a portion of the dynamite down a brass tube at the bottom of the box.

The girl wraps a small square of branded parchment paper around the bottom of the tube, folding it at the lower end. Then holding the paper with one hand, and jumping up and down as she works the pumping-handle with the other, she pushes dynamite down the tube till the paper cylinder is filled to a depth of about three inches. She then removes it, folds down the top of it, drops it through a slide in the wall, whence it rolls down into her own special box a finished cartridge.

She replenishes her stock of dynamite with a scoop through a sliding door in the wall, from a box of loose dynamite which the runner has placed in a closet chest immediately outside. The girls work with the greatest rapidity. The sliding brass rod is actually lubricated with nitroglycerin. To see this operation – the brass rods flying up and down, damp with nitroglycerin, and dynamite being forcibly jammed down a brass tube – entirely destroys your appetite for further knowledge. It is incredible, and you want to go away, outside the "Danger Area," and think it over.

But your guide takes you instead to a blasting gelatine cartridge hut. Here blasting gelatin, a yellow, tough elastic paste, which consists of about seven per cent. Of nitro-cotton and ninety-three of nitroglycerin, is being forced through a sausage machine, chopped, by hand, into three-inch lengths with a wooden wedge upon a lead-covered table and wrapped into cartridges, at the greatest speed.

Blasting gelatin is fifty per cent. More powerful than dynamite, and the effect on your mind is to make you exactly fifty per cent. More uncomfortable than before; to multiply by one and one-half your desire to get away before any contretemps occurs which you would be in no position to either explain or avoid.

There are forty-five cartridge huts, all heated by steam to not less than fifty degrees Fahrenheit. Nitroglycerin congeals at forty-three Fahrenheit and freezes at forty, so the huts must be kept warm. If the dynamite were allowed to rest against a steam-pipe an explosion might follow, and the pipes are carefully boxed, and the thermometer is always watched by the eye of authority.

In addition to dynamite and blasting gelatin cartridges, the company manufacture cartridges of gelatine dynamite and gelignite, combinations of nitroglycerin, nitro-cotton, nitrate of potash, and wood meal. The gelatin explosives are specially adapted for use under water, being entirely unaffected by dampness of any kind. The company also make Ardeer powder and carbonite – explosives for blasting purposes in fiery coal mines, with a lower percentage of nitroglycerin than dynamite. The output of explosives of all kinds is an average of about one hundred tons per week.

Making nitro-cotton on a massive scale

Nitro-cotton, which by itself and in combination with nitroglycerin as cordite and Ballistite is rapidly displacing gunpowder in every direction, is made and used by the ton at Ardeer. It is made from cotton-waste, the waste left on the spindles in the cotton-mills. This comes to Ardeer in bales, like bales of finished cotton, and is first washed, to remove all grease and dirt, carded, and reduced to a homogeneous mass in a big mill devoted to these processes.

Then it goes to a great barn-like building where it is turned into soluble nitro-cotton or insoluble gun-cotton, as may be desired, the process taking place in small iron pans or hundreds of earthenware jars. Half the floor is taken up by the jars, which sit side by side in a shallow tank of cement about a foot deep. The object of this tank is to keep the jars cool by surrounding them with water during the nitration. Along one side of the room are the acid taps and lead pans.

Four pounds of cotton are placed in a pan, and one hundred and fifteen pounds of mixed sulphuric and nitric acid are added. In a few minutes the chemical combination takes place, the acid is poured off, and the nitro-cotton receives its first washing. From this point, until every particle of acid has been washed out of it, it is liable to burn spontaneously at any instant. As one of the workmen dumps the pan load into the centrifugal or acid separator, it may go up with a flash and a great column of yellow smoke; and this not unfrequently happens, but does no great harm except, perhaps, to beards and eyebrows.

It takes fire slowly and gives full warning. It now goes to another department and is washed repeatedly, kept for a week in water tanks, pulped in ordinary pulping-mills, and dried in rotary centrifugal machines until all but thirty per cent. Of the water is eliminated. The remainder is dried out of it on the shelves of a great drying-house, where a temperature of from 100 to 120 degrees Fahrenheit is maintained by hot air through fans.

At Ardeer this nitro-cotton is used in enormous quantities in combination with nitroglycerin to make blasting gelatin, of which it contributes seven per cent.; and Ballistite, which consists of sixty per cent. Of soluble nitro-cotton and forty per cent. Nitroglycerin. The extraordinary affinity of soluble nitro-cotton for nitroglycerin is a curious chemical fact.

No matter how much water is presented in the mixing-tank, every particle of gun cotton will find and absorb the nitroglycerin, and this wet mixing process as invented and carried on at Ardeer is admirable of its kind. The material for cordite, in the form of cordite paste, is made in large quantities at Ardeer, and sent to the government factory at Waltham, where the government smokeless ammunition is made.

Ballistite is a speciality at Ardeer, and is rapidly displacing the other smokeless powders for sporting purposes. Its admirers claim that it is stronger than any other, cleaner in the gun, perfectly smokeless, and entirely unaffected by heat or dampness. It can be soaked in water and fired without loss of efficiency. Since the professional pigeon shots have largely adopted it, and the weekly scores in the sporting papers show the majority of kills to its credit, the shot-gun fraternity, so numerous in England, have taken to it en masse.

Ballistite is made in three forms: in cubes for cannon, in minute rings for rifles, and in square flakes for shot-guns. As first made and dried, it is a light brown elastic paste. This is run through steel rollers which are heated to 120 degrees till it becomes as thin as tissue paper and transparent. It is like thin, elastic sheets of silky horn. Then it is cut up in cutting machines into grains of various sizes for rifles or shot-guns, as the case may be.

These processes are most ingenious and mechanically interesting, and occupy several large mills by themselves. In all are the thermometers and the shoes. The machinery in nearly all cases represents original inventions, either conceived in Ardeer or invented by Mr. Nobel, who was the originator of smokeless powders. Absolute cleanliness reigns. Dust is never allowed to collect, and the small quantity of sweepings from the leaden floors are daily burned.

The subsidiary departments are full of interest. "India" and "Siberia" are two magazines where the company’s explosives and others from all sources are tested through long periods under high heat and severe cold respectively. India of course the more dangerous, and before entering it your guide climbs a ladder on the embankment which surrounds it and peeps through a three-inch hole to read the thermometer projecting from the roof of the house inside. India caught fire in 1895, and would have harmed nothing but itself had not some over-eager firemen gone inside the banks and attempted to extinguish the fire.

In the explosion which occurred two were killed and two other employees injured. To avoid a repetition of this occurrence a huge sprinkler now rises in the centre of the hut, by means of which at the first sign of fire the whole interior can be deluged from a safe distance. A thermo-electric tell-tale also runs from India to a laboratory.

In the packing houses the cartridges are packed by girls into five-pound cardboard boxes, which in turn are grouped in fifty-pound wooden cases. These cases are taken in hand-cars to the magazines and thence to the beach, the railways running into the sea.

The cases are transferred to boats and loaded into the company’s own steamers, which carry them to all the Channel and neighboring ports for shipment all over the world. There are also sample magazines, an Armoury containing all ancient and modern small arms; a shooting range, with its attendant officers and experts, where the explosives for rifles and shot-guns are carefully tested; laboratories, and contributing departments of all kinds.

The cases are transferred to boats and loaded into the company’s own steamers, which carry them to all the Channel and neighboring ports for shipment all over the world. There are also sample magazines, an Armoury containing all ancient and modern small arms; a shooting range, with its attendant officers and experts, where the explosives for rifles and shot-guns are carefully tested; laboratories, and contributing departments of all kinds.

Remarkable freedom from casualties

Having now inspected the factory in all its interesting entirety, you are confronted with a statement so extraordinary as to be almost incredible, viz., that despite the manufacture by the ton of all these deadly explosives; Ardeer is one of the safest factories that you could possibly be in. In the whole period of its existence, about twenty-five years, the entire loss of life by accidents, including the sad occurrence of February 24th, has been only twenty-one.

This, compared with the number of people employed, is lower than the death-rate in any cotton-mill, woollen-mill, foundry, boiler-shop, shipyard, or other large manufactory. The main cases of this excellent showing is the admirable character of the discipline imposed and the firm and careful system of management. But the rigid, intelligent, and systematic way in which explosive factories are guarded by government regulations and government inspectors undoubtedly also plays a large part in this result.

The nitroglycerin compounds, however, are far from being as dangerous as is generally supposed. Nitroglycerin itself is always a possible source of explosion, but up to this year no accident had ever attended its manufacture at Ardeer. The accidents that have occurred have been due to the handling of it after it has been made. With regard to dynamite, its actual safety as an explosive was ever the pride of its late inventor, Mr. Nobel. He claimed that dynamite could not be exploded by being thrown to the ground from any height; that it could sustain any degree of shock without explosion.

He claimed for blasting gelatin that, in addition to being the strongest, it was absolutely the safest explosive known. In proof of this he devised a series of experiments which have been often performed at the factory and which have never failed. They may be seen at any time by a visitor whom the company desires to convince, and as given on a late occasion were as follows:

1. A cube of iron weighing 420 pounds was hoisted on crossed poles above an ordinary packing box containing fifty pounds of dynamite cartridges, the box resting on a board on the ground. The rope was cut by electrically exploding a cartridge against it, and the weight fell twenty-five feet, smashing the box completely and pulverizing some of the cartridges; but there was no explosion.

2. The same experiment was repeated with a box of blasting gelatin cartridges, the fall being twenty-five feet and the iron weight 470 pounds. Box and contents were crushed and scattered, but there was no explosion.

3. A one pound tin of gunpowder was placed on an open five pound box of dynamite cartridges and exploded. The dynamite caught fire and burned up, but did not explode.

4. The same experiment was performed with a five pound box of blasting gelatin cartridges with the same result.

5. A dynamite cartridge was set on fire by a fuse, and burned rather rapidly. It would have burned away completely, but a detonator had been placed in the middle, and when the flames reached this the other half of the cartridge exploded.

6. To show the strictly local force of dynamite, a one pound cartridge was hung eight inches above a three-eighths of an inch boiler-plate, which was lying on two bits of wood and exploded. The plate was only slightly bent.

7. A similar cartridge was laid flat upon the same plate and exploded, the result being a hole torn in the plate about the size of the cartridge.

8. A similar cartridge was then placed on a similar plate and covered with sand. Upon exploding, it tore a large hole in the plate.

Dynamite and blasting gelatin when set on fire will merely burn away without danger. If compressed, both will burn until the heat reaches a point high enough to explode the remainder, but this always requires sufficient time to give bystanders full warning and enable them to reach a point of safety.

All the nitroglycerin compounds are exploded by detonation; that is, by means of explosive caps like percussion caps which fit on the ends of the fuses. The cap explosion is a mixture of mercury and chlorate of potash, and the Nobel company have a large and separate factory in Scotland which is devoted to the manufacture of fulminate of mercury and various kinds of detonators.

The explosive force of No. 1 dynamite, weight for weight, is four times that of gunpowder. Bulk for bulk, the dynamite being much heavier, it is over seven times as powerful as gunpowder. Blasting gelatin has nearly six times, weight for weight, and a fraction less than ten times, bulk, the power of gunpowder. Gun-cotton and No.1 dynamite are about equal in explosive strength.

The explosive force of No. 1 dynamite, weight for weight, is four times that of gunpowder. Bulk for bulk, the dynamite being much heavier, it is over seven times as powerful as gunpowder. Blasting gelatin has nearly six times, weight for weight, and a fraction less than ten times, bulk, the power of gunpowder. Gun-cotton and No.1 dynamite are about equal in explosive strength.

Dynamite is not allowed on passenger trains in England, but is transported with great freedom on the continent, and thirty thousand tons of it have been shipped on the English and Continental railways without accident to date. Of course, every package and case carry explicit instructions, but that the danger is small the immunity from explosions in transport clearly shows.

The moral of which is, that dynamite is safe and blasting gelatin is safer if they are treated with only reasonable care. The accidents do not occur here but in the use of it, says Mr. Johnston. If the company’s explicit printed instructions were followed, accidents would scarcely be known. Accidents often occur in thawing after an explosive has been frozen; but these arise from the incredible recklessness of miners.

Small accidents, also, transpire at Ardeer in the repair of pipes. A drop of nitroglycerin which has secreted itself in a crack or crevice in the metal is sometimes struck by a hard tool, and costs a plumber one or more fingers.

These facts concerning dynamite are well known, and they are very reassuring. As you enter the train to leave Ardeer, however, the old habit of doubt reasserts itself. A bit of white fluff on our coat sleeve is viewed with the greatest suspicion. The question arises, Is it cotton or gun-cotton?

Nerving yourself to the ordeal, you deliberately pick it off. You then carefully throw it out of the window to wreak its fell purpose. If it has one, on the landscape. Then you settle back with a vague desire to look at a thermometer. You have acquired a respect, an admiration, for any and all thermometers, which will abide with you to the end of your days.