Personal Recollections ~ Saltcoats

I was born in Saltcoats in 1956, at home in Ardrossan Road; and lived there until 1972, when my father was transferred by ICI and we had to move Down South.

We lived at the far end by the Iron Bridge, where the road slopes down to the seafront and the burn, just on the Saltcoats side of the border with Ardrossan. It was a good spot to live. The beach and the Plantation were both no distance at all , the town centre only a short walk down Ardrossan Road, and there was always plenty going on to see out of the front windows.

Trains steamed by under the Iron Bridge; and they were steam trains still when I was very young, with their crimson carriages. Buses in five different colour schemes passed by along the road. There were crowds of trippers in the height of summer; and wedding parties at the registry office opposite and the church a few doors away, cluttering the street with cars and confetti. Even the Queen passed by once; but I missed seeing that, because I'd only just been born.

We weren't locals. In fact we were English. My father arrived in the district in early 1949 when he got a job in electronics with ICI Nobel division at Ardeer. Apparently it was a choice between that and a job in equally-unfamiliar Liverpool, and both my parents liked the idea of living at the seaside .The disillusionment came sooner rather than later; the first thing my Dad found the need to buy on arriving in the area to live was a pair of waterproof over-trousers!

We weren't locals. In fact we were English. My father arrived in the district in early 1949 when he got a job in electronics with ICI Nobel division at Ardeer. Apparently it was a choice between that and a job in equally-unfamiliar Liverpool, and both my parents liked the idea of living at the seaside .The disillusionment came sooner rather than later; the first thing my Dad found the need to buy on arriving in the area to live was a pair of waterproof over-trousers!

My mother and my sister Anne, then aged two, joined him a few months later when he'd settled in and found a place for them all to live . A few possesions and pieces of furniture followed them north: a Utility bed that had been bought on the newlyweds' ration; some second-hand donations from relations. They all came by rail, one or two at a time, neatly crated up for the journey; the station vanman and his horse became old familiars as they brought things round the short distance to Arran Place, where the family had taken an upstairs flat at the Robertsons' , beside the Barony Church. Some Stevenston folk may remember Mrs.Robertson, who taught at St.John's primary there.

It was their first proper start to family life together after several years of living with relations; and they were glad to have such friendly and welcoming neighbours as the Robertsons to introduce them to local shops and doctors; and this whole new world north of the border with its sometimes slightly strange ways. Like the Scottish approach to the Christmas season, for example. My Dad remembers their astonishment on their first Christmas Day when the coalman turned up with a delivery of coal . And he was only at home himself because he'd taken a day of his annual leave, because back then it was a normal working day at the factory; there were three days off for New Year instead though !

A few years later the family moved to the house in Ardrossan Road. It was a bit run down after the years of war and austerity; and my dad, being good at DIY and fixing things, did quite a lot of the home improvement work himself over the next few years. Getting the kitchen in order was the first priority ( the primitive state of things didn't suit my ex-domestic science teacher mother at all ! ) ; and the tale is still told of my Dad's exploits demolishing a bed recess in the front kitchen to make more space. One blow of the hammer and it all collapsed in a heap around him; it had been built up just of loose material and ashes. But that being all it was , when the dust settled my Dad found to his surprise that he was still in one piece, even if the bed recess wasn't !

The kitchen was completed with that ultra-modern luxury, a fridge. And then there was the television, just in time for the Coronation of 1953. A great way to get to know the neighbours, as everyone from our end of the road came round to watch it. There were the Gibsons and the Perrys, and Mrs Wood; and the registrar's family the Brysons, who lived " over the shop ". Innocent Anne let the cat out of the bag to her schoolfriend from the Free Church manse, so that family had to be invited as well; the minister put a bit of a damper on the party since he turned out to be rather dour and disapproving. There must have been at least twenty people including assorted children , all crowded into our ( luckily quite big ) front room round one small TV screen. Some of them must certainly have had to bring their own chairs; I know Mrs. Wood brought along an old child-sized chair for Anne, a gift that was later passed down to me. Meanwhile the Bryson baby slept peacefully through it all in the back room ( a likely story considering the Typical Boy he grew up into ! ) ; where my mother had also laid out some refreshments. Altogether it was the nearest Ardrossan Road got to a street party. Not very near, admittedly; this was staid Ardrossan Road, after all !

A few years on , and some of my first social experiences came in visits to the neighbours. On one side lived the widowed Mrs. Wood, all alone in a big old-fashioned double-fronted house. The kitchen was so antique it had a stone-flagged floor; the main front room, which we visited most, was full of heavy Victorian furniture. There was a grandfather clock, a big seascape hung on the wall over the fireplace, but my favourite thing was a rocking-chair; where I would enjoy sitting while my Mum chatted to Mrs. Wood. She can't have been all that old , because she lived on into the 1980s, but she seemed so at the time; she dressed in a very old-lady style, and rarely went out . But she seemed to know all about everything that was going on in the district just the same.

The Gibsons' house on the other side was very different: light, bright, well furnished- and- carpeted in up-to-date style. The main attraction for me here was a little musical-box, with a ballerina who came up and danced. Mrs.Gibson, a cheerful grey-haired lady whose children were mostly grown up and gone, was my mother's first resort in a domestic crisis; I remember her coming in the day I got my finger stuck in a door, though funnily enough nothing at all of all the fuss and bother there was getting me out again!

Our two houses were a pair - you couldn't quite call them semi-detached because ours was built on to Mrs.Wood's earlier house - and I was always fascinated by the idea that the Gibsons' house was the same as ours back to front. Especially since we had a big mirror on the party wall in the hall, so it was quite literally "through the looking-glass ". What was through the mirror was what I could see in the mirror; except it wasn't, because the Gibsons' house was nothing like ours... no surprise that the adventures of Alice became some of my favourite books.

Our house was more " lived in " than theirs. My toys found their way in everywhere, even the front room, big enough to swallow up them as well as everything else that was needed to make a cosy, rather than elegant, sitting room. As well as the television we had a piano and, at first, a wind-up gramophone to keep us entertained.  Both were donations from my mother's rich Auntie Vi, the family benefactor in those days.The gramophone was a special children's one decorated with nursery rhyme characters, with a set of records to go with it, though by my day they had been added to with everything from Bing Crosby to Tommy Steele. I think it was probably a hand-me-down that had previously belonged to Auntie Vi's doted-upon only son Rex, like a number of children's books we had; but it was still a generous gift, and we got other things that were definitely new...pretty frocks with elaborate smocking that were handed down from Anne to me; a Fortnum's hamper and a Harrods' turkey every Christmas. Auntie Vi hadn't always been rich; in fact she spent most of her childhood in a grim Victorian orphanage, separated even from her sister; but when she grew up she married her boss, a successful businessman, and lived in a country manor house. And her experiences having left her with a strong family feeling, she liked to share her good fortune .

Both were donations from my mother's rich Auntie Vi, the family benefactor in those days.The gramophone was a special children's one decorated with nursery rhyme characters, with a set of records to go with it, though by my day they had been added to with everything from Bing Crosby to Tommy Steele. I think it was probably a hand-me-down that had previously belonged to Auntie Vi's doted-upon only son Rex, like a number of children's books we had; but it was still a generous gift, and we got other things that were definitely new...pretty frocks with elaborate smocking that were handed down from Anne to me; a Fortnum's hamper and a Harrods' turkey every Christmas. Auntie Vi hadn't always been rich; in fact she spent most of her childhood in a grim Victorian orphanage, separated even from her sister; but when she grew up she married her boss, a successful businessman, and lived in a country manor house. And her experiences having left her with a strong family feeling, she liked to share her good fortune .

The Back Room behind was a bit of a glory hole; its miscellaneous uses included spare bedroom, workroom and playroom, and it was heated only when needed, with a small wall-mounted electric fire. My Dad kept his tools in the corner cupboard and Fixed Things on the same big solid table also used for ironing and sewing, crafts and hobbies, and even ping-pong. Being built on a slope, the house was all on different levels, so from the two main rooms at the front there were several steps down to the kitchen and dining area, and then more steps down to the back garden. The bathroom was up one flight of stairs, the bedrooms another floor up. This meant the main downstairs rooms had fantastically high ceilings; but the bedrooms were low, tucked under the eaves.

I had my own tiny bedroom when I was old enough; seven feet square and only half of it full height. The wardrobe with my clothes in had to sit outside on the landing ! But I loved my little room, and I still have fond memories of choosing a carpet for it ; at a sale in a warehouse on what I think was my very first trip to Glasgow, with some men turning over a hung-up pile of pieces for me until I fell in love with one covered with splashes of lots of different colours.

Our garden was long and thin, with a gate at the bottom onto the lane that runs between the backs of the houses of Ardrossan Road and Montgomerie Crescent. When I was five we had a garage built there, one of a semi-detached pair to match the houses, put up by the Gibson family building firm; Mr Gibson himself worked on the job. I enjoyed playing in the garden .There was a swing where my big sister would push me , and a sandpit; I could make mud pies or make friends with the snails and the caterpillars; or "help " with the gardening. But a gate closed off the side yard, keeping me away from the drains and the piles of coal .

Every so often a coal lorry would come up the back lane, and the coalmen tramped up the garden path with the heavy sacks on their backs to replenish the heap. No central heating in those days; it was cold bedrooms upstairs, and coal fires downstairs, with all the trouble and mess that went with them, especially when the sweep came and everything had to be swathed in dustsheets. Coal lorries piled with sacks were one of the most commonplace sights you could see in the streets in those days. Other deliveries came too, but they were more often. A weekly box of groceries was " sent up " from Wilkie's; and then there was my favourite caller the Laundry Boy , from Munro Cleaners, where we sent the big washing like sheets, since we had no washing machine .

I wasn't allowed out in the lane on my own either when I was little. But I didn't mind that much, because it always seemed too quiet and lonely out there, with nobody about. When we walked along it there was very little to see; just walls and gates and in some places, mostly on the Crescent side, the big blank doors of garages. The walls were higher on that side, some with barbed wire or bits of glass on the top, and ivy creeping over. In the dark it could seem quite spooky. Especially spooky to me was the sign on the wall where the side lane came in ; a ghastly white pointing hand, with under it the words " No Thoroughfare ". It showed up in our car headlights as we drove past, completely ignoring its sinister warning that our part of the lane was a Dead End. I wasn't surprised at all when I found out that the name of the place was Eerie Lane; at least , that was what the street sign said, up at the town end. When, years later, the council replaced this old, half-broken sign with a brand-new one I was really quite disappointed to learn that Montgomerie Lane was its proper name !

GOING SHOPPING

Eerie Lane was just one part of the interesting world there was to see not far from home.The shore, the plantation, the Glebe; I gradually came to know them all and the streets around as we explored on Sunday walks. Then just over the Iron Bridge there was Moir and Rooney's corner shop; we went over there quite a lot, and sometimes we would come back with choc-ices or ice-lollies out of their little frozen cabinet. But that shop closed down when I was about five. Ever after I would pass it, still there with its blue blinds down, sad and empty.

But for serious shopping we would walk straight down Ardrossan Road to town, with me skipping over the cracks between the paving stones and pestering my mother with questions; off to visit the proper shops of Saltcoats. I enjoyed going shopping with my mother when I was little. There were so many different places to go and people to meet as we wended our way round the town every day, going from shop to shop as you did in the far-off pre-supermarket days of the late fifties and early sixties. Progress could be slow, as my Mum passed the time of day with shop people and stopped to chat with other shoppers in the street; she was well plugged in to the local grapevine after just a few years in town.

There were plenty of shops to choose from. I've been counting up the ones from the earliest I can reliably remember. Just in the town centre, and not counting any in the parts I didn't know over the railway and out in the schemes, there were at least a dozen groceries and dairies ; about seven bakers and six greengrocers; three fishmongers, five chemists, a hardly credible ten or eleven butchers' shops. Everyone had their own favourites. Wilkie's the grocers, Thomson's the butcher; Gordon's for fish and Fleming's for greengrocery; Ross ' Dairy and Howie's bakehouse; Cox's the chemists and Veronica's newsagents; you can read all about these and many more in A Stroll Round 1960s Saltcoats.

And, home again, like as not I would soon be playing at shops, with the assistance of my favourite " toys": a collection of grocery packets and containers my mother had saved for me, kept in a box in the cupboard under the stairs where the proper groceries also lived. The simplest toys can sometimes be the best, and what hours of fun I had with these.

SUMMERTIME

In summertime, holidaymakers still flocked in great numbers to Saltcoats back then. At Glasgow Fair time especially the town would be packed with trippers.  They thronged the fair and the amusement arcades, the bathing pool and the Pavilion, they crowded the shops and the pubs, and all the umpteen cafes, tearooms, restaurants and carry-outs of the town. I remember times when you would struggle to get around the central streets even on foot, let alone in a car, there were so many people in town. Dockhead Street was far from being pedestrian in those days; hard to credit it now, but it was packed with two-way traffic and the pavements were so narrow in places that you needed to walk in single file: a scary business with big lorries maybe growling along right beside you. ( I named my toy lion Lorry, because he roared ). But at holiday times the traffic just had to give way, and the people reclaimed the streets.

They thronged the fair and the amusement arcades, the bathing pool and the Pavilion, they crowded the shops and the pubs, and all the umpteen cafes, tearooms, restaurants and carry-outs of the town. I remember times when you would struggle to get around the central streets even on foot, let alone in a car, there were so many people in town. Dockhead Street was far from being pedestrian in those days; hard to credit it now, but it was packed with two-way traffic and the pavements were so narrow in places that you needed to walk in single file: a scary business with big lorries maybe growling along right beside you. ( I named my toy lion Lorry, because he roared ). But at holiday times the traffic just had to give way, and the people reclaimed the streets.

Meanwhile up at our end of the town special trains would be disgorging crowds of passengers at South Beach station, built with an enormously long platform for that very purpose. Charabancs lined the seafront, and increasingly too there were parked cars all along outside our house and in the other roads near the beach. The council chambers in Montgomerie Crescent behind our house ( now replaced by flats ) blocked the view of the seafront from the back of our house, but if we raised the frosted window of the bathroom and peered out we could just about see the beach, so densely packed with trippers it seemed black with them; and hear the great hum from all these people coming up from the shore.

We were able to choose much quieter times to go to the beach. We had what seemed like our very own secret route; through a sliding panel in the back gate opposite ours, and through the grounds of those same council offices. We would slosh and flounder through the thick layer of pebbles there was round the building, enjoying the racket it made, laden down with stuff for the beach: buckets and spades and an inflatable beach ball, a bag with towels and things, and even a folding deckchair. Mum would usually sit on that in state while the rest of us paddled, built sandcastles, wandered the pools and the rocks and the islands of dune grass that seemed to get bigger every year. And finally watched the tide creeping in, changing the landscape, washing away our castles, bringing to a close our timeless afternoon on the sands.

There were other pleasures exclusive to summer. Best of all was the annual visit of my paternal grandfather and his sister Auntie May, all the way up from Shropshire in England. My Dad would take his holiday from work and off we would go most days with a picnic, all six of us packed into Grandad's bigger car, with me on Auntie May's lap ( no seatbelt laws in those days...no seatbelts, come to that ! ), exploring the seaside and countryside around.

I loved seeing the world like this; going round all sorts of strange and interesting new places, and then the reassuring surprise when we suddenly came back to somewhere I knew. In those early days we didn't stray too far from home. We went up to the other beach at North Shore; or over Fairlie Moor, with the sheep and the heather and the fantastic views of the Firth of Clyde that were even better through my Grandad's binoculars. Along the back road to West Kilbride, picking blackberries; or inland to the woods and lanes round Blair House, where you could buy fruit from their gardens.

Largs was a favourite spot; on the road into town there was even a " Welcome to Largs " sign, and on the back of it as you left it said " Haste Ye Back ". I particularly enjoyed the childrens' rides they had on the promenade then, before they were swept away in the later sixties to make way for Harry Kemp's monster amusement arcade the Cumbraen. They suited me rather better at that age than the alarming excitements of Saltcoats Fair with all its noise and bustle, where I timidly stuck to the tamest of rides . Also on Largs prom was an aquarium in a sort of caravan, with lots of colourful tropical fish; and of course there was ice-cream from Nardini's, which tasted quite different from Cavani's Saltcoats ice-cream. Their shop was much more glamorous too; it seemed to me then like somewhere out of a film. In fact all the cafes and tearooms of Largs seemed a lot grander than the ones in Saltcoats. But on the other hand I was very unimpressed with their beach, just a little stretch of pebbles !

I still sometimes think of a lovely sunny day as " a day to go to Largs on ". But the sun didn't shine all the time in summer; far from it. I remember one year it rained practically the whole time Grandad and Auntie were with us. Running out of time to enjoy the local scenery, we set out one afternoon hoping it might be clearing up; but once we'd got far enough away from home, down poured the rain again. The Loch Thom hills we'd hoped to visit were invisible; it was early closing day in all the shops; and we ended up bringing our picnic home and sitting eating it on our new green frontroom carpet, pretending it was a grassy field...Even the most loyal Threetowner would have to admit : it does rain an awful lot on the Ayrshire coast.

STARTING SCHOOL

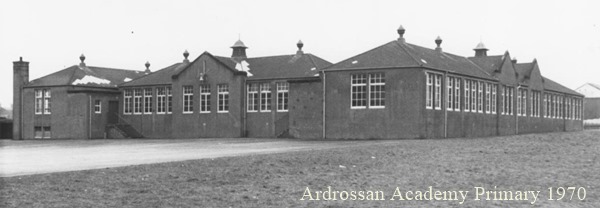

My big sister Anne was my favourite companion. But every weekday she was absent, off at a place called school. One foggy day we saw her through the plantation; she went up the steps at the top and vanished into the murk, and that was as much as I knew of the school for big boys and girls she went to, Ardrossan Academy. I had no idea it had a primary school, which it still did back then, nor that I would end up going to it; I had been led to believe that when I started school it would be at Saltcoats Public, a familiar landmark in my world.

I've already related elsewhere how bewildered I therefore was when the time came to go to school ; and how the disconcerting experiences of that day ended with me seated ignominiously at the bottom of Miss Miller's class. And back then that sort of thing mattered, even at our tender age of five.

For once we got going Miss Miller streamed her class into four colour-coded groups, red at the top, then blue, yellow and green at the bottom, with the top rows forging ahead faster. Regular tests, every week I think, had us moving up and down the class. And how cross I remember being at having to work my way up right from the bottom. It must have seemed a reasonable way to our teacher of coping with a very large class of beginners, all progressing at very different rates; but it was also an all too early introduction to the rat race that was traditional schooling in those days.

Everything about school was pint-sized to match us at the beginning; infant-sized desks and chairs, even half-sized cut-down jotters, which filled up with our early attempts at writing and sums...and if we were lucky, a selection of gold, silver and red stars for good work. But I was quite pleased to find that it wasn't quite all reading and sums at school as I'd expected. We got to play with plasticene, and do painting; we also started learning to sing. Miss Miller had her own piano in the classroom, and she began teaching us some simple hymns like " Jesus Loves Me " and " All Things Bright and Beautiful "; for the fourth R, Religion, was as important as the other three in those days, if not more so. I remember being caught inattentively staring out of the window one day, and being required to come out to the front and sing by the piano; oh the embarrassment...

We also had the Primary music teacher Mrs McDougall come in to us. She draped a long solfa chart over a little free-standing blackboard, and we learned our do-re-mis; or sometimes she brought in a box of percussion instruments. I longed to be given one of the more exciting ones like a tambourine , but somehow it was always a triangle as usual. Another more awe-inspiring occasional visitor was the Rector of the school; we all had to stand up when he came in and chant " Good morning ( or afternoon ) , Mr Macfarlane. " His visits were our only real contact with the big school across the playground.; he seemed a rather remote and austere figure, then and afterwards.

The school world outside the classroom was even more daunting at first. We little ones were a bit lost among the crowds of bigger children who thronged the playground. Boys rushing around or playing football jeered at me to get out of the way. Even worse were the big girls who roamed around with linked arms chanting " join on, join on ", who swept me up on one occasion wanting to know " what's your favourite colour, who's your boyfriend ? ". I didn't even know any boys, and didn't much want to from what I could see of them .... Others had bigger siblings to look out for them, but Anne was far away round at the big school. But we were watched over more than we knew . One day, to my surprise and relief, a bigger girl who had been harassing me was summoned to Miss Miller's classroom and though I had never said a word about it she was told off in no uncertain terms for this and other misdemeanours; she never bothered me again.

It took me a while though to feel part of things and get to know some of my classmates. There were so many of them: 44 of us on that first day, and we stayed in the mid-to-high-forties throughout; big classes were the norm in those days. They all seemed to come from faraway Ardrossan, and lots of them to know each other already.

In fact the first I remember making friendly overtures to me weren't in my class at all. One week, Miss Miller was away and as generally happened in those days we were divided between other classes. There were two intakes a year then and the " February Class " just ahead of us was the one I found myself in. We spent at least a week there and perhaps their teacher had suggested they make their guests welcome, because to my surprise I found myself befriended by two dark-haired girls called Christine and Anne. Which was really very nice, though I wasn't entirely sure about Anne, because she seemed to be a bit naughty....But alas, none of this continued when we went back to our own class; the unwritten rule that different classes didn't mix reasserted itself, and it wasn't till we were in the same secondary class that I got to know naughty Anne properly once again.

MY SISTER

Still , at least there was my own big sister Anne to walk with to and from school; after the very earliest days when we didn't go for a full day and my Mum collected me in the middle of the afternoon, I always went with her.Going to school in the morning we took the shortcut through from South Crescent to the plantation: down the little lane there was then between St Andrew's Church and the burn, onto the platform of South Beach Station, and over the bridge that used to be at that end of the station, to join the path from Bute Terrace. This bridge had an even better claim to be an Iron Bridge than the more famous one a few yards away along the track, because whereas that had wooden treads, on this one even the steps were metal plates riveted together.

We would usually meet up on the way with some friends of Anne's, some of them also with younger ones in tow, plus my favourite Ponytail Pamela who came on the train. We might go along and call in at the Cabin before heading up South Beach Road; I was suitably shocked to see the big bad boys buying illicit cigarettes. Or more often we wandered up the path beside the burn, over the bridge built out of rustic logs, and up through the top corner of the plantation, where the trees were dense and housed a noisy rookery , and the path was sandy and full of roots. We would dawdle in at the school gates just as the janitor was tolling the bell that hung over the Primary Hall...cutting it a bit fine as far as I was concerned, being supposed to be standing in line to go in on the other side of the building by then !

I was in the plantation other times of course, but my fondest memories of it are of walking to and from school with Anne; for every spot on the way I can call to mind some incident, or something she told me. Here's where she dropped her mirror, and told me breaking it meant seven years bad luck; here's where I was surprised to see the moon in daytime, and she showed me the Man in the Moon. Here's where she and her friends hotly debated the rival merits of History and Geography, and I was required to promise to choose Geography when I grew up; and here's where they dashed off to save a small boy from a big dog armed only with an umbrella.

The years passed, and by the time I was nine Anne had left school, one of the Duxes of the Academy, and gone off to university in York , determined to fly the nest . And before long she was off altogether to a job in London, returning only for high days and holidays, usually in some clapped-out old banger of a car that needed a trip to McCully's garage before the visit was over. I got to borrow her bedroom when she was away; I was growing out of my little one a bit by then. Otherwise I missed her, and the sheer stimulation of her company. She'd occasionally done the teenager thing and grumpily shut me out of her room, but more often she'd been happy to let me join in, to push me on the swing and play games with me; especially board games and card games, for which she had a passion. And from my earliest years I'd looked on in awe at some of the fascinating things she did: from playing the piano to developing her own photos, from knitting jumpers in fiendishly complicated patterns to making working models with my Dad's old Meccano set. ( If you think no girl ever voluntarily played with Meccano, think again ! But in spite of her example it never appealed to me. ) Even a look at her homework had fascinated me; would you believe I couldn't wait to grow up and do exciting sums with letters as well as numbers.

Having a teenage sister also gave me a precocious interest in pop music.; I became an avid viewer of Juke Box Jury and Top of the Pops, and counted down the charts on a Sunday night on the big dining room radio. This was a huge item by modern standards, relying as it did on valves, and sat on its own special shelf; what a liberation it was when Anne got one of the new transistor radios that you could carry round the house.

Since Auntie Vi's gramophone only played 78s, by now we also had a red Dansette; I loved the way you could put a whole pile of records on it and play them one after another. It was Beatles records now that dominated our turntable, and I was first in the queue to go and see the Beatles films when they came out. There were no screaming girls among the audience, thank goodness, but many of the youngsters there stamped along during the songs, which was almost as bad. This was all at the Countess, one of three cinemas then in the town; it was in the Town Hall of all places, the council having had the brilliant idea fifty years back of letting out this white elephant for the purpose. I loved every part of the cinema-going ritual, from the moment when the lights went down and the curtains swished aside, right down to coming out still dazzled with it all to catch a bus home in the dark.

But television was our main entertainment. What other programmes did I enjoy most ? Mr Pastry and Harry Worth. Blue Peter for its informative features; Crackerjack with its fun and its quizzes; and indeed quizzes of all sorts, soaking up general knowledge like a sponge. Top Cat and the Flintstones; Yogi Bear and Deputy Dawg. Animal Magic with Johnny Morris, who reminded me of my grandfather. The Sunday classic serials, introducing me painlessly to famous literature. Dr Who, from the very first episode. Bewitched, and Tich and Quackers. And The Man from Uncle, for which I stayed up late on Thursday evenings; my entire generation of nine-year-olds, I've since discovered, was doing the same.

MORE SCHOOL

Back at school, I had progressed by now through several classes: though Miss Taylor's I missed quite a lot of due to several prolonged spells of illness . Every time I came back there seemed to be a new seating arrangement; Miss Taylor was experimenting with sitting us in groups, though all firmly facing the front at this stage. Once I even found myself sitting next to a brand-new classmate; several joined us that year, raising our numbers to 48. Miss Taylor kept order by having us all put our faces down on the desk for a while when the class got restive. But one day we re-emerged to discover she had quietly gone round and given us all a chocolate bar. This must have been at the end of the year I think; a farewell gesture in return for us ( rather enterprisingly for our age ) buying her a leaving present. And she wasn't the last to go.

Miss Banks was our next teacher; the only really young class teacher in the whole of the Primary.Later she married and became Mrs Jack. Friday afternoons in her class always ended with a spelling quiz , with the different rows competing with one another. Then it was Miss Reid. Our studies were getting more serious now: we started on Geography and History with her, and embarked on long division and grammar. She did at least choose a gentle way to introduce this latter, by reading us a story called The Grammatical Kittens, one episode, and grammatical term, per week; the fact I still remember it suggests it was a good ploy.

Meanwhile things had been changing for the Academy primary. With the new Stanley School opening, the powers that be had decided that the intake behind ours should be the last, and the school began gradually to be run down. As we all progressed up the school and classrooms emptied, they were colonised by classes from the overpopulated secondary department. These bigger invaders crowded the corridors at times but were far too lordly to pay any heed to us.

More positively, we younger ones increasingly had the run of a much less crowded playground at break times. The monitors who'd overseen things seemed to disappear when we got to around Primary 4, and those of us who preferred chasing games and role play over skipping ( a skill at which I was quite hopeless ) roamed happily around the wilder parts of the school grounds when we got the chance, behind the huts and around the coal heaps, getting up to less than sensible things sometimes. Sheila was our leader; the bliss of being invited to join her group lives still in the memory. She said what went; and I never questioned the ruthless playground politics which had us feuding intensely with anyone who thought different and tried to set up in rivalry.

As numbers dwindled, so too did the staff of teachers; the older ones retired, younger ones moved on to other schools. But the one who seemed oldest of all, Mrs Blythe, stayed on almost to the end. Lack of alternatives saw us having her for two years in a row , so our time with her looms large in my memories. Everything about her seemed old-fashioned: her white hair was kept in a bun ;in the age of mini-skirts hers were nearly to her ankles. And she had no qualms about giving the strap to misbehaving boys, though as with all our primary teachers she was never belt-happy, unlike some of the teachers of that era.

Nothing more typifies Mrs Blythe's classes than the attention she gave to religious instruction. We went to an assembly in the primary hall every morning, but that didn't stop her having further hymn-singing when we got back to the classroom, followed by a session of Bible study; we got a thorough grounding in both Old and New Testaments during our time with her.

But the other notable feature of our years in Mrs Blythe's class was the amount of Scottish history and culture we imbibed. We learned the poems of Burns, and went through the whole of Scottish history from Kenneth McAlpine to Bonnie Prince Charlie, using a book called The Story of Scotland. Most of our textbooks were as old as the hills, with the names of multiple previous owners recorded on a sheet inside the front cover , to which list we added our own; but what makes me think this was a special project of Mrs Blythe's is that these were brand new, and she thought so much of them that she gave a special lesson when we got them on how to cover your books, with paper provided .The theme continued with Mrs McDougall teaching us Songs of the Isles , and the primary gym teacher Miss McKelvie , to whom we had now graduated after the early years of having our own teachers do gym with us, starting us on Scottish Country Dancing. Even someone of English family like me was thoroughly Scotticised by the end of it all.

Up till now our education had been as ultra-traditional as you can get. But this was to change when we arrived in Primary 7. So many teachers had left by now that they actually needed to hire some new ones . And they were even reduced to employing students to teach us for the first month of the new term, before they could find someone more permanent. In our case this was Mrs Maclean; who having taught in England was full of up-to-the-minute ideas. And once our qualifying exams were out of the way, we had great fun putting these into practice.

We were among the last to take " the qually "; and in our case , apart from a formal printed paper for an intelligence test, the decision was made on the basis of our normal school exams, sat just before Christmas with slightly more formality than usual, with the two senior classes being mixed together in alternate rows to diminish potential collusion. The Academy primary always had a higher pass rate than average, and with an increased number being let through that year about two-thirds of us were selected to continue at the Academy. But this division was a more temporary one for our generation than in the past, for with the Academy turning comprehensive we were reunited in the same school a couple of years later. It's telling that some of those who came back , and were given the opportunity to take courses and do exams that they mostly otherwise wouldn't have had, did better than others who had passed; providing proof of the fundamental unfairness of the old division into sheep and goats.

Then after Christmas it was all change for a more progressive education. Not that progressive of course; we were still following our traditional subjects, experiencing the joys of parsing and decimals. But we began to spend increasing amounts of time finding things out for ourselves, using a class library of reference books Mrs Maclean had found from somewhere; working through work cards, and compiling projects: Mrs Maclean was very keen on Projects. And we found ourselves only too happy to humour this apparent eccentricity, particularly when it came to working in groups. Before long, she had the desks pushed together and us seated in sixes, all named after Great Britons like Nelson and Churchill ( we chose these ourselves, on very conventional lines; it never so much as crossed our minds to consider a woman ) ;and facing each other rather than the front of the class. A refreshingly sociable experience, particularly when it came to the girls and boys interacting, something we had rarely done over the years.

There were other liberating activities: elaborate craft projects, like making big collages ( my group did a beach scene, with the Beatles in the bandstand and Concorde flying overhead ) and trying to make life-size figures out of papier-mache ...oh, what a mess we made ! We went to the beach to collect shells, and then cemented them onto boards as shell pictures. We measured the school building and drew a plan of it to scale; we put on a play called A Japanese Legend, with everyone but the heroine conveniently costumed in dressing-gowns. We kept fish from the burn in a tank in the classroom ( they didn't survive long ); we sold our mothers' baking round the classes to raise money for charity. And as the year drew to a close we spent whole afternoons in the field playing rounders, and afterwards stayed sitting out there while Mrs Maclean read us Tom Sawyer. It was an idyllic end to our Primary days.

ALL CHANGE

And so after the summer holidays, we came back to begin our secondary days . We girls had our own brief private reunion on the first morning, the old comforting ritual of greeting each other for the start of the new term; before separating for good into the different streamed classes into which the Academy divided us. Most of us were also to be in different classes from the boys for the first two years; as much a matter of administrative convenience as any particular policy, I suspect, and indeed there was one experimental mixed class that year. The boys' Latin stream was labelled 1:1, the girls' class 1:2 , but this order of priority was merely a mild annoyance; we girls knew we were superior to boys any day.

It was startling to look upon the sea of new faces in the classroom and realise that they would all become familiar classmates over the next few weeks. Exciting to see the timetable filling up with new subjects and some of the legendary teachers my sister had told me all about: I would soon be fielding enquiries after Anne from them, and from some of the new young teachers who had been her near-contemporaries. I doubt if they were any wiser than I was when I told them she had become a Systems Analyst.

Anne had also drawn me a helpful plan of the school; a very necessary aid to finding my way round in the first few days. We had visited the main building from time to time during our primary days, mostly for special occasions like concerts and prizedays, but most of it beyond the main halls had stayed a mystery to us ; now we were ranging not only over that but all of the numerous huts and outbuildings the school had sprawled into. Including of course our very own primary building, where we were now the interlopers and the last primary class had been banished to a hut.

But the old primary building wasn't to be our stamping-ground for much longer. Little over a year later, plans were announced for the Academy to turn comprehensive, and to make the necessary space to accomodate an enormous 1500 or so pupils much rebuilding would be needed. There were to be two multi-storey classroom blocks, plus a new dining hall and a sports centre; to make room for these the primary building and half the huts had to go. But since these were all fully occupied with classes , and demolition work was due to begin almost at once, something had to give; some pupils would have to be decanted elsewhere.

So began a game of Musical Schools, with pupils all over Ardrossan and Saltcoats ending up on the move. The signal to begin was the completion of the new Dykesmains Primary; the primary pupils from Saltcoats Secondary school at Jacks Road could then move into it, leaving space at Jacks Road for the 1st and 2nd year Academy pupils. I was in 2nd year by then, and part of the exodus. We pupils rather enjoyed the upheaval, and our awayday at Jacks Road. It was quite a recent building, and we marvelled at the modern facilities, such as indoor toilets, unheard of at the Academy. It was the teachers who bore the brunt of things; while the two schools were officially amalgamated and we had a few of the Jacks Road teachers for classes, for the most part it was our usual teachers who were having to commute back and forth between the two buildings, forever dashing off to catch the minibuses and taxis that had been laid on for them. Meanwhile demolition of the old primary had proceeded apace, and by June 1970 the frames of the new buildings were rising. True, it had got a bit run down in the past few years; but we were sad to see it go , a whole chunk of our lives torn away.

Things got even more complicated in the next school year when Stanley School, then also a secondary school, was also brought into the mix. A complete comprehensive intake started out in 1st year there; 2nd and a few 3rd years continued at Jacks Road; while 3rd to 6th years were at the old buildings. And there were even more minibuses and taxis , shuttling now between three sites. But school life managed to carry on without descending into complete chaos; and by the end of the year the new classroom blocks were nearly finished, ready for a grand reunion of the school on the old site at the start of the next session.The other schools involved also took on a new lease of life; Stanley became an enlarged primary, while Jacks Road was handed over to become the new Catholic St Andrew's Academy, with St Peter's pupils moving in there.

For old-timers like me, the new school opening was a disorienting process. It felt a bit like being five again; feeling a bit lost among all these new buildings and crowds of strangers. Even the old building was changed : the science and practical rooms had all been converted to ordinary classrooms; the girls' and boys' cloakrooms had been inexplicably swapped over; and the sacred Front Door, previously strictly reserved for teachers and visitors, had become just another door to be used every day. Suddenly too there were years of younger ones coming up behind us. Because of the run-down of the primary, we had actually never known that situation before ; and it turned out to be rather fun to meet and chat with the younger siblings of classmates and their friends, getting their take on the brave new world of comprehensivisation; we started feeling like wise elders who'd seen it all.

And if it sometimes felt as though I was at a totally new school, not Ardrossan Academy at all, that was just a preview of something that by now I knew was about to happen to me in earnest . For ICI had been undertaking a major reorganisation, and the fallout for us was that Dad, given the choice between redundancy and redeployment, had opted for a move down south, to Manchester , and I would be leaving my familiar world behind me very soon.

It was like our family's arrival in town in reverse. Dad went ahead to start his new job , coming home every few weekends; Mum and I stayed behind for a year, so I could complete my O Grade exams.In the meantime, we cleared out the detritus of a quarter of a century and began packing up our lives.I squirrelled away all the memorabilia I could find; something to look back on when I was far away from home.

I had never been to England; everyone had always preferred to come to us for visits. When I was very little, I thought it was just a bus-ride away; I looked with fascination upon the people getting on the New England bus, wondering why we didn't join these compatriots of ours and just go there ! Now I read up with anxious interest on this foreign land to which I was going, with its strange customs like A-levels instead of Highers, and its football teams with funny names; partly familiar from TV and books, but different in so many ways from home. Manchester in particular, with its surrounding Northern industrial culture, was completely new to me. Apparently it was notorious for its rain; well, that at least wasn't going to faze a native of the Three Towns.

It was raining the day we left Saltcoats in May 1972. As our heavily-laden car drew away from our back gate down the lane, it began to pour; and all the way down through the hills and along Nithsdale to Dumfries we were buffeted by the wind and the rain. But as we neared the border it stopped; and by the time we were in the environs of Manchester an evening sun was gilding the city, lighting up all its red-brick terraces . And as we arrived in the southern suburb where we were to live, I found to my surprise that we were surrounded by trees; an unexpected delight and partial recompense for the loss of the seaside. Our new home was putting on its fairest face for us; perhaps things weren't going to be so bad after all.

Susan Nock - England